THINK BEFORE YOU LEAP: OUTSMARTING THE BIASES THAT HOLD ARTISTS BACK

THINK BEFORE YOU LEAP: OUTSMARTING THE BIASES THAT HOLD ARTISTS BACK [T-H-I-N-K]

As artists, we pride ourselves on our intuition—but sometimes our minds play tricks on us. Whether you’re deciding which show to apply to, whether to raise your prices, or how to interpret feedback, there are mental shortcuts (called cognitive biases) that can quietly steer you off course. Awareness is power. Here are 6 of the most common biases that trip up even the most seasoned artists—plus how to navigate them with clarity:

The Spotlight Effect

This is the belief that everyone’s noticing you—when they’re not.

Example: “I didn’t post my new painting because I worried people would notice that I reused a color palette from an older piece.”

Truth is, most people are focused on themselves—not your every move.

Takeaway: Don’t let imagined judgment stop you from showing up and sharing your work.Sunk Cost Fallacy

This is when you keep going with something—not because it’s working—but because you’ve already spent time, money, or effort on it.

Example: “I’ve spent months developing this painting series, paid to frame and photograph it, and even built a portfolio around it. But it’s not getting any traction. I don’t want to give up after investing so much.”

Smarter question: “If I hadn’t already invested in this, would I choose to move forward with it today?”Confirmation Bias

We all like to be right—but this bias causes us to seek out information that supports what we already believe, while dismissing or ignoring anything that contradicts it.

Example: “Every time I post my art on Instagram, I get a few comments saying ‘love this!’ So I know there’s a big audience for my work. I just need to keep posting.”

But if those comments never turn into sales, you might be clinging to validation rather than looking at the full picture.

Better move: Use both data and feedback to guide your efforts—not just what feels good.Gamblers’ Fallacy

This is the belief that past outcomes affect future results—when in fact, they don’t.

Example: “I’ve been accepted to this gallery’s annual show three years in a row—so I didn’t update my application this time. I assumed I was a shoo-in. But I didn’t get in.”

But each year brings different jurors, submissions, and competition.

Smarter mindset: Treat each opportunity as brand new—and give it your best effort, every time.Self Serving Bias

This is the tendency to credit yourself for wins—but blame outside forces for losses.

Example: “My last show was a hit because my work is great. But this one flopped because the crowd wasn’t buying and my booth location was terrible.”

That may be partly true—but lasting growth comes from asking: “What role did I play in this outcome?”

Tip: Stay curious, not defensive. That’s how you level up.

6. Anchoring Bias:

Anchoring bias is the tendency to focus on the first piece of information you receive when making decisions.

Examples:

“That gallery owner said my work reminded them of a famous artist and they’d ‘love to work together.’ So I didn’t follow up with other galleries—I was sure that one was in the bag.”

“A collector said they’d commission a large piece from me. I got so excited I bought supplies, cleared my schedule—and they never followed up.”

But unless you gather real details—budget, size, timeline—it’s just a maybe.

Pause. Ask questions. Stay grounded.

Creativity thrives on freedom—but your art business thrives on clarity. Knowing your mental blind spots is the first step to making wiser, more confident decisions.

CHOOSE WISELY [k-n-o-w]

“We are the average of the five people we spend the most time with.”

~Jim Rohn

[g-r-o-w]

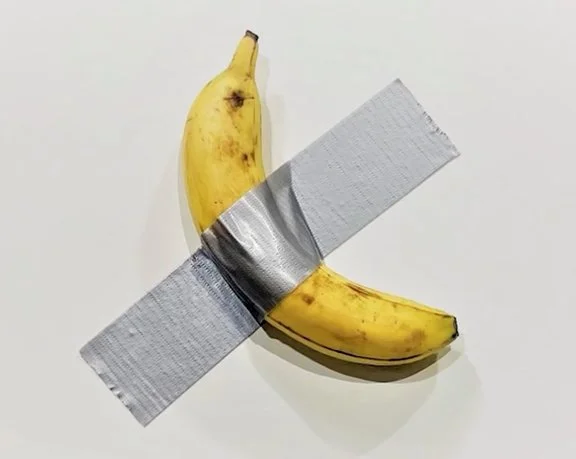

The famous banana duct-taped to a wall at Art Basel (Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian) is a perfect case study in multiple cognitive biases at work in the art world. Here are a few that likely played a role:

BANDWAGON EFFECT

People often adopt beliefs or behaviors because others are doing it. Once a few influential collectors and media outlets praised the piece (or simply talked about it), others joined in—less because they genuinely valued the banana, and more because everyone else seemed to.

ANCHORING BIAS

The moment a price was attached—especially a high one—it anchored people's expectations and perceptions about the piece’s "value." They started rationalizing why it must be worth that much.

AUTHORITY BIAS

Maurizio Cattelan was already a well-known, successful artist. People often assume that if someone of high status does something, it must be meaningful or brilliant—even if it’s literally fruit on a wall.